“Junk Science”: The problematic Jefferson-Hemings “conception window” statistical analysis

Without objective scholarship comes the risk of fiction. Hence, history becomes an illusion.

– Cynthia Burton

Only in fiction do we find that the loose ends are neatly tied. Real life is not all that tidy.

– Walter Cronkite

After the infamous Jefferson-Hemings DNA study in November of 1998, Monticello set out to conduct its own study:

On December 21, 1998, Dr. Daniel P. Jordan, president of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, appointed a research committee of Monticello staff members, including four Ph.D.’s and one medical doctor, and charged the committee with evaluating the DNA study of Dr. Eugene Foster and associates, assessing it within the context of all other relevant historical and scientific evidence, and recommending the impact it should have on historical interpretation at Monticello.

Former surgeon and volunteer Monticello guide Dr. Ken Wallenborn was a Monticello Research Committee member who noted what he saw to be a biased exercise in searching for any form of damning evidence to prove Jefferson fathered Sally Hemings’ children:

When the committee was assembling for one of its meetings in February 1999, the head of the Archaeology Department at Monticello [Fraser Neiman] dropped a packet of papers on the table next to me and said (and this is exactly how another member of the committee and I recollect it): “I’ve got him!” He repeated this statement again and then explained his ‘Monte Carlo Simulation.’ This just seemed to be an inappropriately enthusiastic remark for someone who is working at Thomas Jefferson’s home.

Fraser Neiman’s statistical study, or “Monte Carlo Simulation”, analyzing Jefferson’s residence at Monticello when Hemings’ children were conceived, was dubbed by the USA Today as the “most provocative finding” of the Monticello Research Committee’s report. However, the study was published in a non-scientific magazine with no official peer review. When scientists and statisticians analyzed the study they criticized it for its core mistakes and bias. Professor of Law and History David N. Mayer pointed out the fundamental flaws in the way the conception window analysis was applied:

The Monte Carlo approach estimates the probability of a given outcome by comparing it to a very large number of random outcomes generated by a simulation model. Neiman’s study rested on two unsupported postulates: that there could only be a single father for all of Sally Hemings’ children, and that rival candidates to Thomas Jefferson would have to had to arrive and depart on the exact same days he did. Here, the assumption of random behavior makes little sense, because the visits to Monticello of the other candidates for paternity—Jefferson’s friends and relatives (including his brother Randolph, Randolph Jefferson’s [five] sons, and the Carr brothers)—were not random occurrences; they certainly would have been far more likely to occur after Jefferson’s return to Monticello from extended absences in Washington or elsewhere. The final impression one gets of the Niemen study is of a simulation whose parameters were deliberately set to “get” Thomas Jefferson as the father of Sally Hemings’ children. (Scholars Commission p.302)

Dr. M. Andrew Holowchak described Neiman’s process as a fait accompli:

Neiman has gotten the results he had desired to get, simply because he has plugged in exactly the sort of data that would assure him of those results. Change the data and you change the results.

Thirteen eminent scholars reviewed the DNA study and the Monticello Research Committee Report over the course of a year in 2000-2001.The goal was as Thomas Jefferson described, “to follow the truth wherever it may lead”, and in the process demonstrate proper historical and scientific scholarship. The “Scholar’s Commission” examined Neiman’s statistical study and came to a more likely lower probability of Thomas Jefferson paternity:

Even without considering Thomas Jefferson’s advanced age (sixty-four) and health, if the question is changed from trying to place a single suspect at Monticello nine months prior the birth of all of Sally’s children to simply trying to identify the Jefferson men who were likely to have been in the Monticello area when Eston Hemings was conceived, the statistical case for Thomas Jefferson’s paternity of Eston, based on DNA evidence alone, falls below fifteen percent. (Scholars Commission p.10)

Dr. Wallenborn also described how Neiman was informed of basic editorial mistakes that ultimately went uncorrected:

When his article was listed in Appendix I of the TJMF Research Committee Report and simultaneously published in the William and Mary Quarterly in January 2000, it contained a serious and glaring error that had been pointed out to him. This error was his statement that the “molecular geneticists found the Jefferson Y-haplotype in recognized male-line descendants of Thomas Jefferson”! He should have said descendants of Field Jefferson, Thomas Jefferson’s uncle. Why the TJMF allowed this significant error to be published in their report and in the W&M Quarterly remains unanswered. Future historical researchers will possibly quote this erroneous statement and think that the DNA sample came directly from Thomas Jefferson’s direct descendants and that this cinches the case in the Sally Hemings paternity story.

Neiman’s statistical analysis makes a number of reaching assumptions in order to build a statistical case, but without those assumptions, the entire statistical model falls apart. For example, Neiman refuses to acknowledge a number of key possibilities: that another Jefferson male could have impregnated Sally, that Sally might not have been monogamous, and that either Sally or Jefferson might not be present at Monticello during her conceptions. An honest statistical model cannot be computed without factoring in such alternative hypotheses. For example:

- Sally may have conceived elsewhere. There are no comparable records establishing Sally Hemings’ whereabouts during the same period. Monticello’s own tours describe how slaves were sometimes given a “slave pass” which allowed them to travel off the mountain. Slaves such as Sally’s sister Critta were also sent out to work at other farms, and evidence indicates that Sally may have been absent at Monticello at times. There is simply no record of Sally’s comings and goings. (Jefferson Vindicated, p. 106)

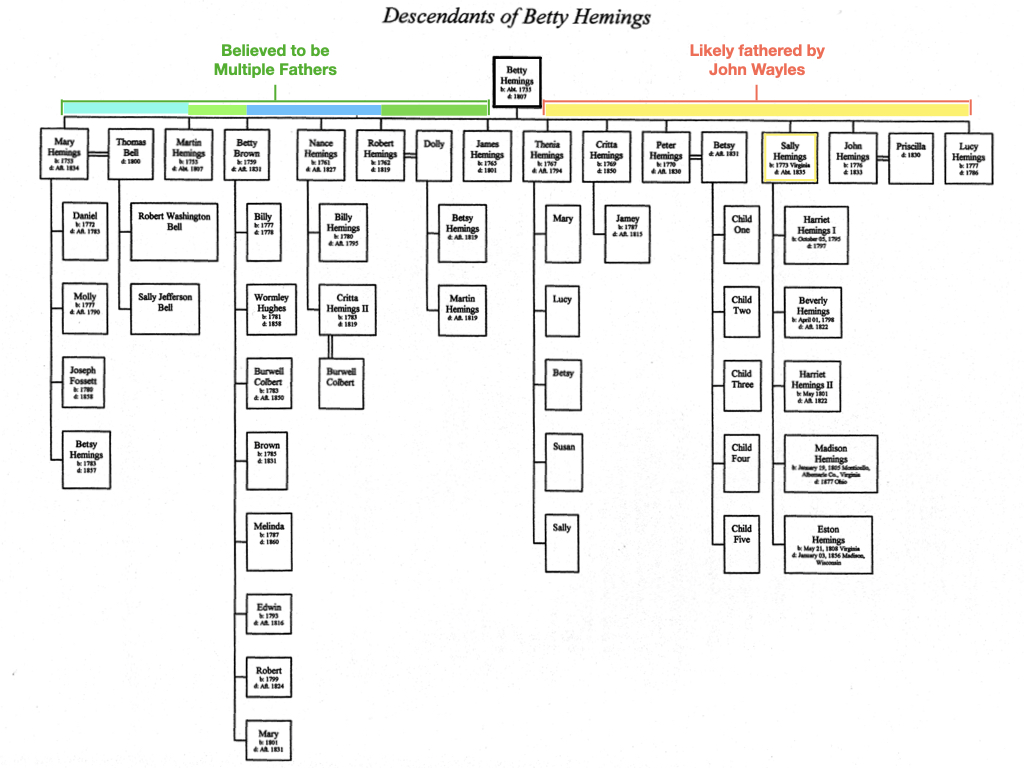

- Sally may not have been monogamous. Unmarried women who have multiple children may have them by multiple fathers. Sally’s own mother and two of her sisters each had multiple children by multiple fathers. For example, Sally’s older half-sister Bett was the mother of eight children by multiple men.[1] Madison Hemings said Sally’s mother Betty Hemings “had seven children by white men and seven by colored men — fourteen in all.”[2] As former slave Henry Bibb wrote in 1849: “It is almost impossible for slaves to give a correct account of their male parentage….”[3] This was an unfortunate reality at the time, and it is entirely possible if not likely that Sally could have fit the pattern. Historian Eyler Coates: “But the Monticello report states, in effect, that because Sally’s patterns of conception match Jefferson’s presence at Monticello it should be taken as evidence that all her children were by the same father, i.e., Thomas Jefferson. In this way, the committee uses one assumption to support another.”[4]

- It is impossible to assume all the dates of births were accurate. The dates utilized for the study were from Jefferson’s own hand-written farm book, which he loosely maintained when he was away as President and often made entries months later and sometimes years afterward. For example, when he returned to Monticello after a long absence, he asked others to inform him of their recollection of the dates of any slave births that occurred while he was gone.

- Another Jefferson male relative could have been the father, particularly of Eston Hemings. Dr. David Murray, Director of the Statistical Assessment Service describes, “[T]he act of appearing at Monticello should not be viewed as itself a causal procreative act. The Report’s mathematical model is likewise incapable of ruling out the prospect that Thomas Jefferson’s visits to Monticello co-occurred with some other event, such as a visit by nearby brother Randolph (or any other of the crowd who traveled with the president), who comes to see his brother just when his brother is there. This is not idle speculation, since a record was found at Monticello showing an invitation to Randolph to visit Thomas Jefferson exactly coincident with [the conception window for Eston Hemings]. But because no one found a record of Randolph’s actual arrival, the Report declines to pursue the Randolph connection…. It is equally possible to declare that [other Jefferson males] were present but unrecorded as it is to claim that no other Jefferson male was ever-present during those time periods.”[5]

In fact, the biggest oversight of the theory and statistical study is the refusal to acknowledge any other Jefferson male as a paternal candidate. Sadly, many historians — and even “Jefferson scholars” — have not taken the time to study the lives of Jefferson’s male relatives, let alone as candidates for paternity.[6]

Dr. Wallenborn said that the committee as a whole seemed to be actively trying to avoid an honest consideration of other candidates as if a pre-determined result was being sought.[7] This mindset drove the statistical study, which historian Eyler Coates described:

It begins to appear obvious that the model was set up to produce the desired results, and was not realistically designed to take into consideration other possible explanations. It was designed to indict Jefferson, and it should come as no surprise that the conclusion confirms such a high probability as was “discovered” by such a ruse.

Dr. Murray also noticed a pattern of bias that managed even to make its way into the statistical equation:

It is nevertheless instructive to see how the [Monticello] Report handles the absence of evidence in other circumstances. We don’t know where Sally Hemings was at the time of conception. Of this, the Report can only say, “There is no documentary evidence suggesting that Sally Hemings was away from Monticello when Thomas Jefferson was present.” That is, we see a double standard. When there is no documentary evidence that brother Randolph was there during a conception date, the Report concludes that therefore he was not…. By the Report’s insistence, Sally Hemings is there unless proven otherwise, while Randolph is not there unless proven that he is.

Similarly, Dr. Murray noted how the Monticello Report avoided recognizing Tom Woodson as the possible first son of Sally Hemings (Woodson descendants had no DNA match with Jefferson DNA), since it would disprove the Report’s insistence that Sally was monogamous:

The same maneuver is applied to Tom Woodson, who is dismissed as Sally’s child because there is no documentation of his birth to her, even though oral history links him to Sally quite strongly.

Tucked away in one of the footnotes to the statistical analysis is Neiman’s unsupported reasoning as to why there can be no alternative male candidates:

Because the model outcomes are tabulated against Jefferson’s arrival and departure dates, the probabilities that result apply to Jefferson or any other individual with identical arrival and departure dates. The chances that such a Jefferson doppelganger existed are, to say the least, remote.[8]

Yet Neiman never describes how he determines the “remoteness” of such an individual, and never in the study is it considered for computation. Strangely, Neiman’s “remoteness” seems to be a function of the assumption that either Jefferson sired all six children or the doppelganger is some one who likewise fathered all six children. Why should it be assumed that there is one and only one person who must tread in Jefferson’s exact chronology? Dr. Murray addresses the assertion and describes how the study should have been constructed:

That demand seems to follow from nothing more than the previously formed assumption that Sally was not promiscuous. From a probability point of view (and especially given the awkwardness of Tom Woodson’s [non-Jefferson] paternity), there could have been doppelganger sub1, who matches Jefferson’s itinerary during only one stay, and who is responsible for only one child, and then doppelganger sub2, who matches Jefferson’s itinerary on another occasion, and fathers another Hemings child, and so forth. Maybe six doppelgangers, maybe only two or three; who knows? Moreover, maybe it’s someone already at Monticello throughout the period continuously, who therefore doesn’t have to “match” Jefferson’s comings and goings, but is just opportunistically “there” and takes advantage during circumstances that present themselves when Jefferson is coincidentally home. And so forth. I am not arguing that we have evidence of these scenarios. But it would seem that those likelihoods must at least be specific and allowed to function in the model as alternative hypotheses, and not just dismissed. As it stands, the argument sticks with only the most unlikely character, the one perfect Jefferson doppelganger – who presumably also wrote a parallel Declaration of Independence – who is offered as the [only] logical alternative.

Dr. Murray goes on to characterize Neiman’s simplistic yet faulty logic:

Neiman’s argument appears to be something like this: “If Thomas Jefferson fathered children, then Thomas Jefferson must have been present when those children were fathered. Children were fathered at Monticello. Thomas Jefferson was present at Monticello when children were fathered. Therefore, Thomas Jefferson fathered those children.”

Regardless, Neiman asserts with full certainty that the statistical study proves beyond a doubt that Jefferson is the father of all of Sally Hemings’ children. Neiman declares:

…the chance is just 1% that [Jefferson’s] presence was a coincidence…. How likely is it that this could have occurred by chance if Jefferson was not the father?

But Dr. Murray proposes a simple analogy to better illustrate the scenario:

Imagine vases were broken on six different occasions at Monticello. No vases were known to have been broken when Thomas Jefferson was away. Thomas Jefferson was home when all six vases were broken. There is evidence that some Jefferson [male] likely broke one of the vases. There is no evidence that Thomas Jefferson or indeed any Jefferson broke any other vases. Are we willing, therefore, to subscribe to the conclusion that there is a 99% probability that Thomas Jefferson broke all six vases? Mercifully, courts of law are not likely to do so, there being no necessary connection between being present and the act of surreptitiously shattering glass.

When speaking to the press, Neiman asserted not only confidence about his statistical analysis, but also its own historical significance:

“The DNA evidence applies to only one child. This shows he, in all likelihood, fathered all six. Serious doubts about [Thomas Jefferson’s] paternity of all six children cannot reasonably be sustained. This statistical analysis is more powerful… than the genetic finding.”[9]

Rather than publish his statistical analysis in a scientific journal and submit it to peer review, Neiman solicited a cursory review by two demographers he personally knew and published the study in the William and Mary Quarterly, a humanities journal of early American history and culture.

Similar to the way Dr. Foster published his DNA “historical analysis” in a science journal with no peer review, Neiman published his “statistical analysis” in a history journal with no peer review.

Steven Corneliussen, a science writer at the Thomas Jefferson National Laboratory, felt the need to understand the findings since the national lab he worked for carried Jefferson’s name. After he examined both Foster’s DNA study and Neiman’s statistical analysis, he was shocked and labeled them both “science abuse.”

According to Corneliussen, scientific participants in the controversy – who were not scholars qualified to put the results into historical perspective – abused science’s special authority, leading to misreporting that hobbled public understanding. The flawed statistical analysis only made things worse, and Corneliussen described them both as “intellectual disrespect: abuse of the special authority of science.”[10]

Whether or not Hemings and Jefferson had children together, misreported DNA and misused statistics have skewed the paternity debate, discrediting science itself.

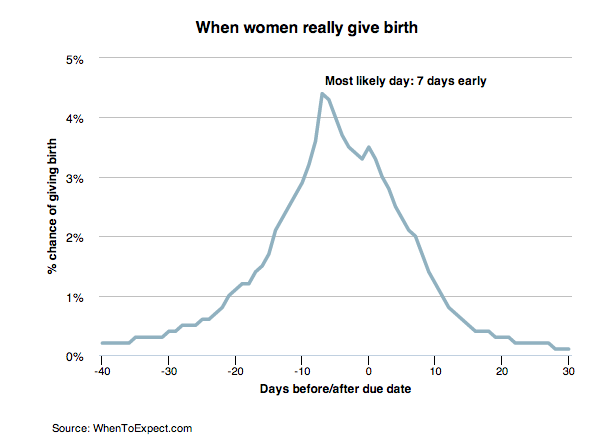

Neiman made fundamental errors that statisticians recognized immediately. Neiman had merely established an exact calendar date of 267 days prior to birth for the conception date of each of Sally Hemings’ children. However, Neiman had overlooked the simple reality any parent knows: births rarely ever occur precisely 267 days after conception, the presumed average gestation length.

In reality, conception windows are a bell curve that spreads over the period of as much as five weeks, which should include at least three weeks before and two weeks after the presumed conception date.[11] The US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences states that “only 4% of women deliver when predicted and only 70% within 10 days of their estimated due date.”[12] That means that one in 25 women give birth on their due date. Neiman failed to account probabilistically for variability within the four-to-five weeks conception window, which throws off the computations of the entire statistical analysis, particularly when Jefferson was only present at Monticello briefly around the time of conception date. The Scholars Commission noted how Jefferson’s absence from Monticello reduces the statistical likelihood significantly:

It is also inaccurate to say that Thomas Jefferson was at Monticello nine months before each of Sally’s children was born… Using Dr. Nieman’s figures, for example, we find an estimate that Beverly Hemings was conceived on July 8, 1797 (a nine-month gestation would have begun on July 1), and that Thomas Jefferson had not been at Monticello since May 5 and did not return until July 11. While it is certainly possible that Sally did not become pregnant until after the estimated conception date, it seems somewhat more likely statistically that she conceived prior to Jefferson’s return. Roughly ninety percent of mothers give birth within two weeks of their estimated due date, permitting us to identify a four-week conception window during which Beverly was likely conceived. For more than sixty percent of this conception window, Thomas Jefferson was not present at Monticello…. if, based solely on his visitation patterns, the odds are that Jefferson was not the father of Beverly Hemings, it follows ipso facto that there is less than a fifty-fifty chance that he was the father of all of Sally Hemings’ children.[13]

Professor Forrest McDonald, a staunch Hamiltonian and critic of Jefferson, was a member of the Scholars Commission and took issue with Nieman’s calculations. He “observed both that the calculations ignored the fact that 1808 was a leap year; and, far more importantly, ignored the fact that Thomas Jefferson was away from Monticello for as much as nine days overlapping Sally’s probable conception window.”[14]

Corneliussen described how the editors of the humanities journal William and Mary Quarterly overstepped their role by publishing a scientific study outside both their mandate and capacity as historians:

In my view, when the William and Mary Quarterly made itself a venue for science, it became obligated to require science’s common practices [such as technical review]… Among the study’s deficiencies is one problem so fundamental that, just by itself, it cancels any possibility of the study contributing usefully. By failing to apply an obviously necessary biostatistical technique, Neiman failed to account for the distinct statistical chance—in one case, greater than fifty percent chance—that at the time of conception in four of the six cases Neiman designated for study, Jefferson could actually have been absent from Monticello.

Expert genealogist Dr. Edwin M. Knights criticized the Jefferson paternity claims, describing how near certainty is needed to ascribe paternity:

Paternity studies, which include both genetic and non-genetic evidence, calculate a statistical probability of paternity. The non-genetic evidence, known as prior probability, is combined with the results from studying genetic loci from one or more alleged fathers. In most cases, a probability of paternity requires a minimum standard value of 99 percent.[15]

Yet Neiman’s statistical analysis — lacking any thorough technical review for errors — became one of the three main pillars to assert Jefferson’s paternity of all of Sally Hemings’ children, joining Foster’s 1998 DNA study and the overarching historical revisionism.

Dr. Robert F. Turner, chair of the Scholars Commission, summed up the expert assessment of Neiman’s conception window analysis:

Candidly, to borrow a term used by several of my colleagues during our Dulles sessions of the Scholars Commission, Neiman’s “Monte Carlo” study struck me as being “junk science” long before I had become involved in a technical discussion with scientists who confirmed its fatal deficiencies. Another term that was used during the Dulles meetings was “GIGO” —computerese for “Garbage In, Garbage Out,” or “if your input is not reliable, your output from the computer will be no better.” As our report reflects, none of us was impressed by it.[16]

Sources:

[1] Cynthia H. Burton, forward by James A. Bear, Jr., Jefferson Vindicated, p. 107, 109

[2] Monticello Report, Appendix E at 21. See also, JEFFERSON AT MONTICELLO 26 n.1.

[3] Lucia Stanton, SLAVERY AT MONTICELLO 21 (1996).

[4] Eyler Robert Coates, Sr. The Jefferson-Hemings Myth: An American Travesty, p.97.

[5] David Murray, Ph.D., The Jefferson-Hemings Myth: An American Travesty, p.120-1.

[6] Annette Gordon-Reed’s book Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy does not once mention Randolph Jefferson or his sons, as if they didn’t exist, since their candidacy for paternity would put into question her entire thesis. Joseph Ellis, author of American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson and who also wrote the accompanying essay to Foster’s DNA article in Nature, in a phone call with Herb Barger revealed that he was unaware that Jefferson even had a brother.

[7] Ken Wallenborn, The Jefferson-Heming Myth – An American Travesty, p.55-68.

[8] Fraser D Neiman, Coincidence or causal connection? The relationship between Thomas Jefferson’s visits to Monticello and Sally Hemings’s conceptions. William and Mary Quarterly, January 2000

[9] USA Today, Jan. 27, 2000

[10] Corneliussen, Steven. Sally Hemings, Thomas Jefferson, and the Authority of Science.

[11] Sarah Kliff, Doctors get due dates wrong 96.6 percent of the time, Vox, Jul 19, 2014

[12] Pregnancy length ‘varies naturally by up to five weeks’, BBC, 7 August 2013

[13] Robert F. Turner, The Jefferson-Hemings Controversy: The Report of the Scholars Commission, p.126-7.

[14] Robert F. Turner, The Jefferson-Hemings Controversy: The Report of the Scholars Commission, p.130.

[15] Edwin M. Knights, M.D., Genealogy and Genetics: Marital Bliss or Shotgun Wedding? Family Chronicle, March/April 2003

[16] Robert F. Turner, The Jefferson-Hemings Controversy: The Report of the Scholars Commission, p.126.