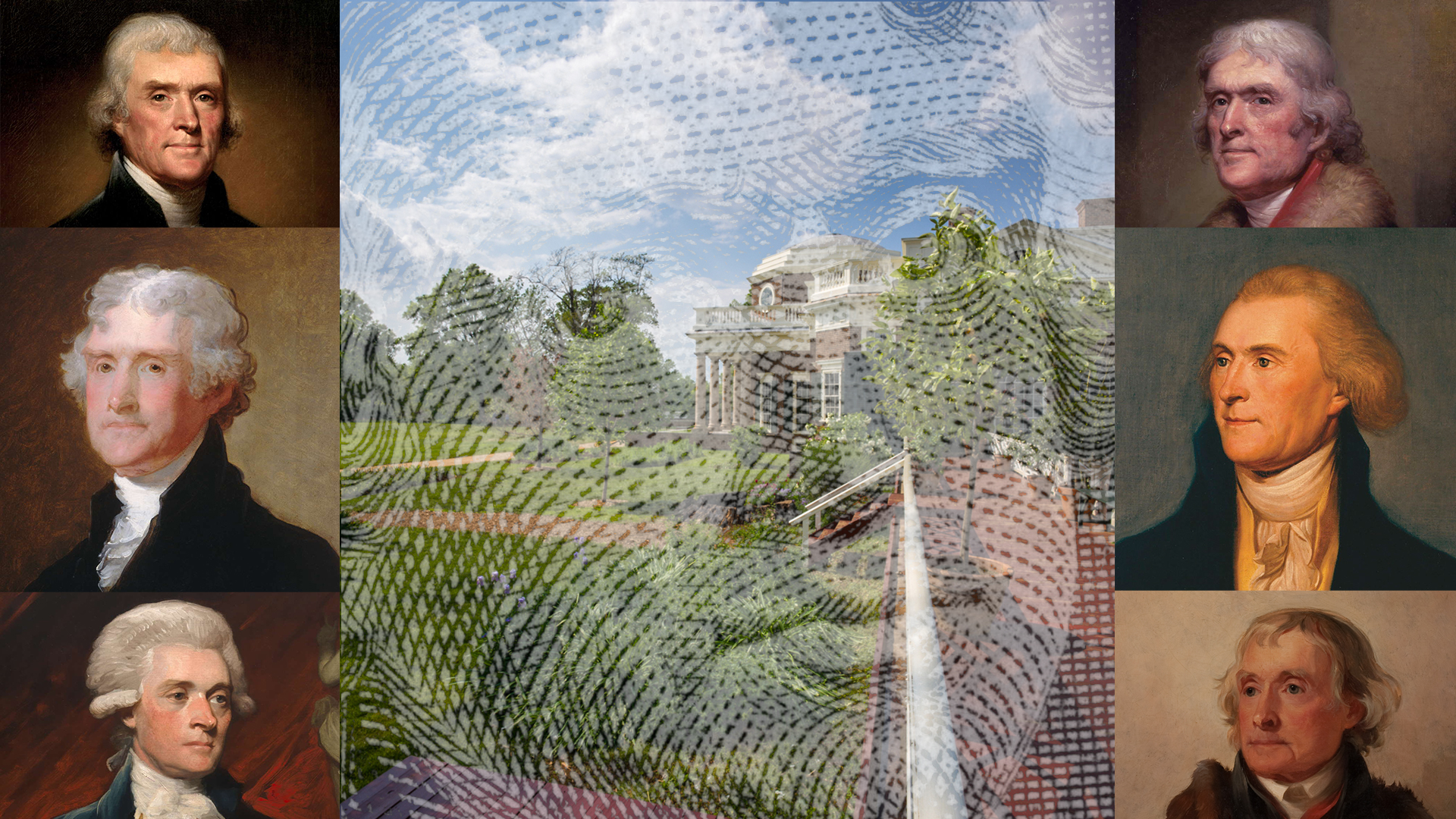

Descriptions of Jefferson’s physical appearance and demeanor

Contemporaries of Thomas Jefferson described him in many ways and even provided colorful anecdotes that give a deeper sense of Jefferson as kind and engaging with everyone without exception. William Wirt, who decades later became US Attorney General, lived in Virginia and described the impressions of a visitor meeting Jefferson for the first time at Monticello:

“… [a visitor] was met by the tall, and animated, and stately figure of the patriot himself, his countenance beaming with intelligence and benignity, and his outstretched hand, with its strong and cordial pressure, confirming the courteous welcome of his lips; and then came that charm of manner and conversation that passes all description—so cheerful, so unassuming, so free, and easy, and frank, and kind, and gay, that even the young, and overawed, and embarrassed visitor at once forgot his fears, and felt himself by the side of an old and familiar friend.”[1]

Surprisingly, there are various conflicting accounts of Jefferson’s physical appearance. For example, few seemed to agree on Jefferson’s eye color. These differences arose likely from the imperfect memories of individuals who only had one or two brief encounters with Jefferson. However, for those who lived at Monticello and spent extended time with him over the years, distinct patterns emerge.

Captain Edmund Bacon’s memoirs describe the years he worked directly with Jefferson as Monticello’s overseer, supervising all activities on the plantation. In his memoirs, he described Jefferson’s physical appearance:

Mr. Jefferson was six feet two and a half inches high, well proportioned, and straight as a gun-barrel. He was like a fine horse—he had no surplus flesh, He had an iron constitution, and was very strong. He had a machine for measuring strength. There were very few men that I have seen try it, that were as strong in the arms as his son-in-law, Col. Thomas Mann Randolph; but Mr. Jefferson was stronger than he. He always enjoyed the best of health. I don’t think he was ever really sick, until his last sickness. His skin was very clear and pure—just like he was in principle.[2]

Monticello slave Isaac Granger Jefferson grew up at Monticello, and his father was its first black overseer. Isaac worked in close quarters with Jefferson and also described Jefferson’s efficient build:

“Mr. Jefferson was a tall straight-bodied man as ever you see, right square-shouldered: nary man in this town walked so straight as my Old Master: neat a built man as ever was seen in Vaginny …. a straight-up man: long face, high nose…. Old Master was a straight-up man.[3]

Others described Jefferson’s unique physical stature in various ways. One said he was “a tall large-boned farmer.”[4] Another said “His limbs are uncommonly long; his hands and feet very large, and his wrists of an extraordinary size. His walk is not precise and military, but easy and swinging.”[5] Many noted his red hair which turned sandy in old age, along with a very red and freckled face.[6] Someone who saw him in his later years said, “He was remarkably erect and had every appearance of antiquity about him.”[7] Monticello slave Israel Jefferson said, “He was hardly ever sick, and till within two weeks of his death he walked erect without a staff or cane. He moved with the seeming alertness and sprightliness of youth.”[8]

Daniel Webster, a Federalist who was in opposition to Jefferson’s politics, met Jefferson when he was eighty-one, just two years before his passing. “His general appearance indicates an extraordinary degree of health, vivacity, and spirit.”[9] When describing Jefferson’s facial characteristics, he noted, “His mouth is well formed and still filled with teeth; it is strongly compressed, bearing an expression of contentment and benevolence.” Edmund Bacon also described how Jefferson always had a peaceful, calming demeanor:

His countenance was always mild and pleasant. You never saw it ruffled. No odds what happened, it always maintained the same expression. When I was sometimes very much fretted and disturbed, his countenance was perfectly unmoved.[10]

He was often described as innately positive: “his manners good-natured, frank and rather friendly.”[11] Isaac pointed out how “Mr. Jefferson bowed to everybody he meet: talked wid his arms folded.” He also described how Jefferson used to “talk to me mighty free” and speak with slaves with dignity. Jefferson “encouraged them mightily. Isaac calls him a mighty good master.”[12]

Bacon noted how Jefferson always seemed to carry an aura of music around him:

I have rode over the plantation, I reckon, a thousand times with Mr. Jefferson, and when he was not talking he was nearly always humming some tune, or singing in a low tone to himself.[13]

Isaac also described how music seemed to emanate from Jefferson wherever he went:

Mr. Jefferson always singing when ridin or walkin: hardly see him anywhar out doors but what he was a-singin: had a fine clear voice, sung minnits (minuets) & sich: fiddled in the parlor. Old master very kind to servants.[14]

William Wirt described how overall engaging and generous Jefferson was in person, elevating the conversation in spirited collaboration:

There was no effort, no ambition in the conversation of the philosopher. It was as simple and unpretending as nature itself. And while in this easy manner he was pouring out instruction, like light from an inexhaustible solar fountain, he seemed continually to be asking, instead of giving information. The visitor felt himself lifted by the contact into a new and nobler region of thought, and became surprised at his own buoyancy and vigor. He could not, indeed, help being astounded, now and then, at those transcendent leaps of the mind, which he saw made without the slightest exertion, and the ease with which this wonderful man played with subjects which he had been in the habit of considering among the argumenta crucis of the intellect. And then there seemed to be no end to his knowledge. He was a thorough master of every subject that was touched. From the details of the humblest mechanic art, up to the highest summit of science, he was perfectly at his ease and everywhere at home. There seemed to be no longer any terra incognita of the human understanding: for, what the visitor had thought so, he now found reduced to a familiar garden walk; and all this carried off so lightly, so playfully, so gracefully, so engagingly, that he won every heart that approached him, as certainly as he astonished every mind.[15]

His granddaughter, Ellen Coolidge, observed and described Jefferson’s temperament:

In private society he seldom or never gave offence to anyone. He was uniformly kind, considerate, and thoughtful of the wishes of others, too courteous to give pain even in trifles, too just not to render to each man his due, and too benevolent not to contribute all in his power to the comfort and satisfaction of all who came within his reach. His powers of conversation were considerable. He was frank, open, and not in the smallest degree overbearing. Young and old took pleasure in his society; and with young and old he conversed readily, cheerfully, and with a most sympathetic spirit; entering into their habits of thought, answering their questions, and putting them completely at their ease, except when inveterate prejudice, or preconceived and stubborn opinion, refused to unbend or to believe. I make no apology for such praise given to so near a relative. Mr. Jefferson has ceased to belong exclusively to his family – he belongs to mankind – and we of his blood should consider ourselves as holding in trust for the use of others that knowledge of his true character which our near approach to him enabled us to become possessed of. His name is often heard, but how few there are who know how much of excellence that name implies.[16]

Sources:

[1] From eulogy on Thomas Jefferson and John Adams delivered by William Wirt at Washington, D. C, on October 19, 1826, in the Hall of the House of Representatives of the United States. “Biography of William Wirt,” in William Wirt, The Letters of the British Spy (New York: J. & J. Harper, 1832), p.76.

[2] Hamilton W. Pierson, Jefferson at Monticello: The Private Life of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Charles Scribner, 1862), 70-71. See Bear, Jefferson at Monticello, 71.

[3] Isaac Granger Jefferson, Memoirs of a Monticello Slave, University of Virginia Press for the Tracy W. McGregor Library, 1951

[4] Augustus John Foster, Jeffersonian America: Notes on the United States of America, (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1954).

[5] Daniel Webster, The Private Correspondence of Daniel Webster, ed. Fletcher Webster (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1857), 364-65.

[6] Augustus John Foster, Jeffersonian America: Notes on the United States of America (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1954).

[7] S.A. Bumstead to “Aunt Lilly,” August 23, 1822, quoted in “A Description of Jefferson,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 24, no. 3 (1916): 310.

[8]Israel Jefferson: Recollections of a Monticello Slave, 1873

[9] Daniel Webster, The Private Correspondence of Daniel Webster, ed. Fletcher Webster (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1857), 364-65.

[10] Hamilton W. Pierson, Jefferson at Monticello: The Private Life of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Charles Scribner, 1862), 70-71. See Bear, Jefferson at Monticello, 71.

[11] Augustus John Foster, Jeffersonian America: Notes on the United States of America (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1954).

[12] Jefferson, Isaac Granger, Memoirs of a Monticello Slave, University of Virginia Press for the Tracy W. McGregor Library, 1951

[13] Hamilton W. Pierson, Jefferson at Monticello: The Private Life of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Charles Scribner, 1862), 70-71. See Bear, Jefferson at Monticello, 71.

[14] Jefferson, Isaac Granger, Memoirs of a Monticello Slave, University of Virginia Press for the Tracy W. McGregor Library, 1951

[15] From eulogy on Thomas Jefferson and John Adams delivered by William Wirt at Washington, D. C, on October 19, 1826, in the Hall of the House of Representatives of the United States. “Biography of William Wirt,” in William Wirt, The Letters of the British Spy (New York: J. & J. Harper, 1832), p.76.

[16] Coolidge, Ellen Randolph. Letters. “Jefferson’s Private Character.” North American Review 91 (July 1860): 107-18.

Image: Portrait of Thomas Jefferson hanging in the Second Bank of the United States Portrait Gallery